73 Years After Internment, Japanese-Americans Still Aren’t Being Given Credit Where Credit is Due

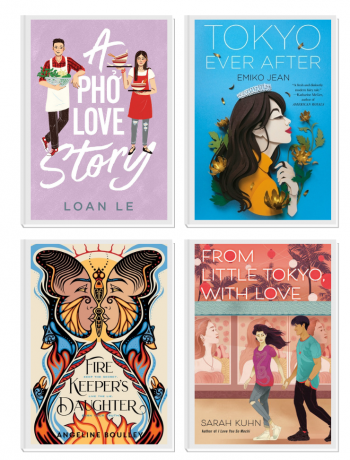

It’s hard to imagine getting angry over tofu. But that’s where I found myself over the last week. The 76th anniversary of the signing of Executive Order 9066 fell on February 19. Each anniversary renews a complicated mix of anger, fear and disappointment for my grandparents and over 120,000 other Japanese-Americans who were rounded up and shipped off to internment camps in god forsaken deserts and swamps for nearly three years. Days later, a few articles about Hippie Food, a new book by San Francisco Chronicle food writer Jonathan Kauffman, popped up on my radar.

Hippie Food illuminates the mostly white personalities in the counterculture revolution who popularized brown rice and macrobiotics, whole grain bread, vegetarianism, and tofu. The emphasis is on those willing to promote themselves as experts and charismatic leaders (a few border on cultish). Even in a book that was researched for five years, the squeakiest wheels get the most ink.

Credit for the “existence” of tofu in America is given to Frances Moore Lappé, author of Diet for a Small Planet; William and Akiko Aoyagi Shurtleff, authors of the Book of Tofu; and Laurie Sythe Praskin, whose Tennessee commune, “The Farm,” was living off mostly soybeans. The existence? No. Oh, come on now, you say, that’s semantics.

There’s no dispute that these people did plenty to popularize tofu in America. The Shurtleffs exhaustively researched and wrote a book that has sold nearly 500,000 copies. The Farm seeded soybean-based products with the people who would go on to start White Wave (oh, the irony), Wildwood and Lightlife Foods, and even the man who created Tofurky. But where are the profiles of Japanese and Chinese-Americans who were making tofu?

The Lens is Always White (thanks to Serena Dai for this line)

In 1970, America was 87 percent white, according to US Census data. So, seen through a white lens, nothing seems amiss with this story. For Asian Americans, statistical insignificance equals historical insignificance, apparently. But in 1975 when the Shurtleffs first published The Book of Tofu, other Asian ingredients, like soy sauce, had been in American kitchens for years, used by Asian Americans who already lived in the United States and brought by war brides in the early 1950s. “By 1954, 333,600 gallons [of soy sauce] were needed to meet demand”¹ in America. In 1972, Kikkoman opened its first US-based factory in Walworth, Wisconsin. And still, in 1972 workers were asked, “How can you work with those Japanese? Don’t you remember World War Two?”²

If that was the reception in the heartland of America, can you imagine a Japanese-American family who’d been incarcerated in an internment camp just 27 years earlier being the squeaky wheel, promoting themselves as tofu pioneers? Ha.

Asian-Americans get barely more than a handful of mentions in Hippie Food’s history of tofu in the United States. We assimilated so well, apparently we should be happy with the crumbs we’re given and let others write history in their own image. Americans were making tofu in internment camps in the early 1940s. Americans were making and selling tofu in grocery stores in the 1960s and 1970s. And yet, none of their stories are included.

Although this is a book is focused on the 1970s, I can’t resolve how you write a book for 2018 America that perpetuates the notion that it was, virtually exclusively, white America’s wanderlust, fascination with Eastern philosophies, and cheap airfares that brought new ingredients, flavors and cuisines to this country. Details of the massive growth of foreign-born Americans between 1960 and 1980 is relegated to the notes section. If only they had stories to tell 40 years later.

In the introduction to Hippie Food, Kauffman raises the very issue of the whiteness of the counterculture revolution:

“One of the uncomfortable, even painful, inadequacies of this movement, which became clear to me with each new chapter I researched, was how white it was….Over and over again, counterculture publications would ask: Why aren’t we reaching nonwhite audiences? Many groups would make a cursory appeal and give up, or settle for one or two token members.”

I would argue, to some extent, Hippie Food has ended up in the same boat. It recognizes and perpetuates the problem in one book.

There was a saying you’d hear over and over again from internees. “Shikata ga nai.” It translates to “Nothing to be done.” Cultural appropriation in food has been widely discussed over the last year or so. Yet, I still found myself surprised at Hippie Food’s paltry recognition for non-white contributions to the foodways of this country.

But there is something to be done.

I’m taking this as an opportunity to research tofu making by Asian Americans. A cursory Google search yields two articles, one about the Ota family in Portland and the Chiu family in Texas. Do them the honor of reading their stories and learning what they’ve brought to their communities and to America.